This is an author who writes literary fiction that is also accessible, warm and wise, witty and clever, despairing and loving – and Transcription confirms all of this. I knew that Transcription, a novel I’ve longed to read, would be every bit as good and I was not disappointed. I fell in love with Life After Life and A God in Ruins by Kate Atkinson. She begins to see faces from the past and she knows that they are due a reckoning. The work of the secret service continues, fighting a different kind of war with a new enemy, and Juliet, now a producer working at the BBC, is about to get entangled again. In 1950 the war is long over but any hopes that Juliet might have that the past is behind her are terrifyingly crushed. But soon Juliet is given a more active role, undercover, becoming perilously involved with the fascists she must spy upon. She also wants to impress her boss, the enigmatic and curious Peregrine Gibbons. It will be Juliet’s job to transcribe their bugged and recorded conversations, a task that both bores and thrills Juliet. They regularly meet in London and are led by Godfrey Toby, a man they believe to be a Nazi spy but who is in fact working for the British secret service. In 1940 Juliet Armstrong, a young woman of just 18 years old, is recruited by the secret service to monitor a group of Fifth Columnists. How foolish to think such a thing was possible, when the Mertons and Fishers of this murky world were in charge of the board.Doubleday | 2018 (6 September) | 337p | Review copy | Buy the book She had thought herself to be a queen, not a pawn. They were all pawns, of course, in someone else’s great game.

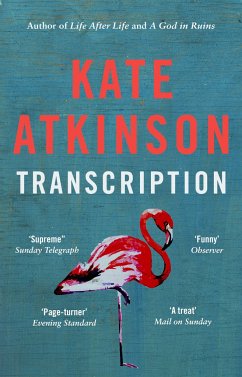

“Life had progressed at such a pace in the previous week that the flamingo’s arrival on her doorstep seemed like something from a dream now. In the depths of her unknowing, Armstrong has only words and associations to play with rather than facts and knowledge. Much of the prose is animated by Armstrong’s interior monologues and asides. But this novel felt like Atkinson didn’t intend for this to be a book as much as a stopping off point on the way to a great BBC series.

Atkinson has never, in all I’ve read of hers, put language before story (and I’m grateful she doesn’t do that here either).

And the prose - although apt and of the time the novel takes place - felt provisional somehow: a hurriedly built set rather than a crafted piece.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)